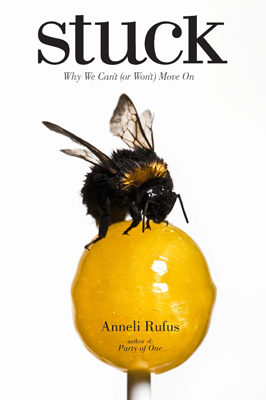

Stuck: Why We Can't (or Won't) Move On

This book explores a striking social trend: many people are stuck, or think they are. They feel frozen. Marooned. Trapped on treadmills. They say they're stuck in the wrong relationships, the wrong careers, the wrong places at the wrong times. They're stuck in bad habits and can't quit. They're stuck the past and can't let go. They're stuck in the present and can't plan for the future. And in many cases, they're looking for someone or something to blame.

How did we get here? Consumer culture certainly has a hand in it, training us from infancy onward to seek instant gratification via various forms of brand loyalty: doing the same things with the same products in the same ways over and over again. But other factors play other key roles, notably fear of change. Tracing the many subtle ways in which American culture often conspires to keep us stalled, Stuck is a work of social commentary that delivers a long-awaited diagnosis for our day and age. For some, there's a light at the end of the tunnel; this book includes stories of people who managed to become unstuck and of others who, after much reflection, decided that they're already exactly where they're meant to be. After all, as the introduction explains: "What looks to you like paralysis looks to others like passion. What looks to you like a rut, others would call commitment, true absorption in a topic, a relationship, a career, a pursuit, a place. What looks to you like boredom, others call commitment. And even contentment."

Praise for Stuck:

Stuck was named by Readers' Digest as one of the Great New Books of January 2009.

Stuck was selected by U.S. independent booksellers as a "nonfiction notable" in the January 2009 Indie Next List:

I was interviewed on the national program "Prime Time Radio" about Stuck.

Excerpts from Stuck:

PAGE 2

In lands of plenty, in the lap of luxury, in the fast lane, we're stuck doing -- over and over -- things we do not want to do. Stuck in places we do not want to be. Stuck with people we do not want to see. Stuck with stuff. Stuck without enough. What irony. You and I will almost surely never be sold into slavery. Those days are gone. We will not become indentured servants, will not be shanghaied and dragged off to sea, locked in the hold, hands chained to oars. We were not betrothed at age ten. That's stuck.

In all of history, no population anywhere has ever been so free as we.

And yet -- somehow we all feel stuck.

PAGE 67

If the most prestigious marvel is the fastest marvel, speed will matter most. If its purpose is to extinguish waiting, time shrinks. Patience atrophies and becomes obsolete. If at a click marvels deliver entertainment, merchandise and sex and all the rest, then we come to mock and despise whatever takes more than an instant and a click. As speed proliferates, we see marvels not as marvels but staples. Speed becomes a basic human right. In 2002, Verizon Wireless debuted a service called Get It Now. This allowed subscribers to download music, videos and other entertainments onto their cell phones: "Watch sports clips, comedy, news and weather from major networks and indie favorites -- all on your phone, on demand," the promo urged. "Express yourself with colorful and stylish images.... Fight boredom with fun games."

But by the time you read this, such technology will already be ancient history. And I will look the fool for citing it, like an old rube in a cartoon trying to feed hay to a car. Cutting edges are disposable blades now, replaced incessantly. We watch, twitching and restless.

PAGE 165

These days, trauma is a commodity. Pain is a status symbol. Suffering brings brownie points. Losers are winners now.

We suckle on stories of suffering. Ours, theirs.

We wade through tales of pain, project ourselves into that hurricane, that hospital, that vestry with that pedophile-of-the-cloth.

Victims are lionized celebrities, sobbing across the screen, the stage, the page. As displayed by the mainstream media, survivors are heroes today less because they survived than because they almost did not. Their pain is the whole point, not their recovery. Their pain is what perverse consumers crave. We have made industries of pain. Trauma now dominates our discourse, infusing each aspect of our lives: news, entertainment, education, literature, with endless variations on it hurts so bad. This revved up in the early 1970s and shows no sign of slowing down.

We compete to see who hurts worst.

We polish scars to shine like stars.