Barnes & Noble

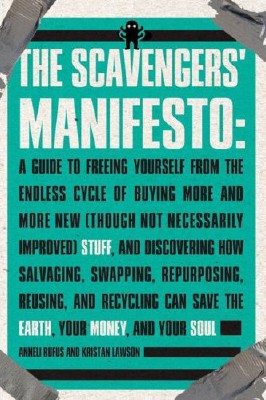

The Scavengers' Manifesto

For more about this book, visit our blog, Scavenging.

A trend is afoot. Millions of people around the world are switching from standard buy-it-new retail toward various forms of scavenging — that is, acquiring things legally by any means that doesn't entail paying full-price. By our definition, a scavenger is anyone who eschews the ubiquitous manufacture-advertise-purchase-consume-discard economic cycle of the modern era. Anyone who delights in the sensation of finding something by chance. Anyone who can't resist free stuff, or who searches for bargains, or who buys something used. Because not all modern scavengers are stereotypical Dumpster-divers. Scavenging should not be equated with distasteful, or dirty, or grungy. Scavengers come in all sorts. The vast majority of us do our finding and foraging in far more sanitary and even middle-class venues: from yard sales to metal-detecting clubs to office clothing-swaps to thrift stores to discount retail outlets to the Internet. Some scavenge to survive, some to save the world. Others do it as a style statement, others to save money. But mostly, we do it for the sheer pleasure of turning life into a series of discoveries.

Thriving right alongside the mainstream, scavenging comprises a powerful guerrilla economy all its own — an alternate realm that's growing bigger all the time. You can see it in the enormous popularity of new movements such as freeganism and freecycling by which thousands of items change hands every day, around the world, without a penny spent.

And this is its manifesto, elucidating not just a crystalline definition of what scavenging is, but also how to do it and what it means. The Scavengers' Manifesto spotlights the philosophy of scavenging, the rationale, the worldview. It examines scavenging as a behavior, as a personality trait — even as an emotion. And it's a how-to guide for those who are still trapped in the rat race but who yearn — perhaps wthout even realizing it — to escape.

Scavenging is any activity that prioritizes chance over choice, surprise over plans, frugality over waste: in other words, having a kind of fun that has largely vanished from modern life.

(Read more about The Scavengers' Manifesto at the publisher's web site.)

Excerpts from The Scavengers' Manifesto:

PAGE 11

The way in which human beings acquire stuff is shifting. Expanding. Forever. All around the world, millions are salvaging stuff, trading stuff, recycling stuff. This is the end of the shopping monopoly.

All around the world, we are scavenging. Today that doesn't mean only the squalid ragpicking it used to mean. So many pursuits count as scavenging today that they can no longer be tucked into any easy little category. We, the authors of this book, redefine scavenging as any way of legally acquiring stuff that does not involve paying full price. Just think how many ways you do this on a daily basis. You scavenge just by tracking down a good bargain.

It used to be that when anyone wanted anything, she automatically rushed out to the store and bought it new, full price. Mission accomplished. Back then — not so long ago — it was assumed that buying things new, retail, was the only way in which respectable civilized human beings could get them. Getting goods by any other means besides store-bought, new, and full price was considered suspicious: fit only for bottom-feeders, moochers, cheapskates, bums....

But times have changed. A confluence of factors — style, politics, technology, ecology, and the economy — have made more and more of us seek more and more alternate means of acquiring stuff. Modern-day scavengers are bold, committed, and resourceful. Goods and services now circle and recircle the world, connecting strangers, not a penny spent.

PAGE 16

Some scavenge for fun. Some scavenge to save. Money. The world. While millions all around us drown in debt, we liberate ourselves with every cent we save while liberating tons of would-be garbage. We know that the difference between brand-new, full-price products and their scratched secondhand counterparts is—

Debt.

Some scavenge to recycle. Repurpose. Reduce. Reuse. They know that some 200 million tons of trash is thrown out every year in the United States alone. In New York City, 64,000 tons per week.

Some scavenge to revolt.

Some scavenge to survive.

Some scavenge for the sake of spontaneity. The long-forgotten magic of the random.

Some scavenge for art. Some scavenge for adventure. Some scavenge for self-sufficiency. For some, scavenging is a test. For some, it's spiritual.

We do not all scavenge for the same reasons, yet we share certain understandings, certain values, certain principles. We share a way of life. A way of looking at the world. Having, each of us, shattered the chains that locked us to consumer culture, we walk free under a clear new sky, scanning a changed terrain studded with buried treasure.

This book is our manifesto and our map.

PAGE 134

Scavenging isn't just fun. It's environmentally beneficial. It diminishes the amount of waste, it eliminates the need for overproduction, it helps to decrease the amount of raw materials being extracted from the ecosystem, and so on. We take this for granted: that one of the main motivating factors to scavenge is that it's good for the planet.

At the same time, in this book we are drawing a connection between the scavengers of today and the scavengers of bygone eras. But the motivations for scavenging back then were completely different. A medieval ragpicker or a nineteenth-century scrap-metal collector wouldn't even know what environmentalism is; but if you took the time to explain it to them, and then asked if that was the reason they scavenged, they'd look at you as if you were crazy. Saving the wilderness was the last thing on their minds. Humans have always recycled and scavenged, but it is only recently that we do so out of altruistic concern for the planet's well-being. Impoverished people in earlier eras scavenged simply because they were trying to scrape out a living, and collecting things of value from the garbage was the only way they knew how. Colonial-era metalworkers and smiths recycled scrap metal and scavenged discarded household objects for smelting not because they were concerned about the effects of strip mining in Bolivia, but because recycled metals were the least expensive way to get the needed materials for their businesses. It's the "invisible hand" of Adam Smith at work again: people take the path of least resistance when making economic decisions, and sometimes it turns out scavenging is the smartest thing to do even when the only thing you're considering is your own profit.

When you scavenge, you absorb other people's pollution like a sponge. Not only do you consume less and thereby decrease your own "economic footprint," when you reuse or recycle other people's trash, you decrease their economic footprint as well. Free stuff, and becoming an environmentalist hero to boot — what's not to like?

PAGE 251

Get off your high horse.

Scavenging has been reviled for centuries because it usually boils down to touching trash. Even in a retail setting, when it has been washed and sorted and priced and set out on shelves and racks, it still counts as trash. Trash that has been donated to thrift shops, carried out of homes for garage sales. Discount-outlet wares are overruns, factory rejects, damaged goods. All might be up for sale, but none are wanted by their makers or their former owners or upstanding front-run customers. Thus all are trash.

This is why we are reviled, but we know better than to revile ourselves or each other or — this matters more — to revile things that cannot help that they have been thrown out. Anyone who ever got his or her favorite chair or slip or coffeepot from a Dumpster knows better. The fact that something was thrown out has no bearing on its worth to its finder. Value is too subjective to be set by such an arbitrary state. One person's trash becomes another's treasure: literally, zillions of times, every day. And who has the last laugh? "It doesn't have to be good to be valuable!" chortles the home page of FreeBay Cyprus, a network devoted to sharing free stuff on that Mediterranean island. Successful scavengers are not squeamish. Successful scavengers are not ashamed.

And scavengers are tolerant. To some extent we have to be, because every act of scavenging is a step out of safe, clean, streamlined, systematic social acceptability. Every act of scavenging renders the scavenger an outsider.